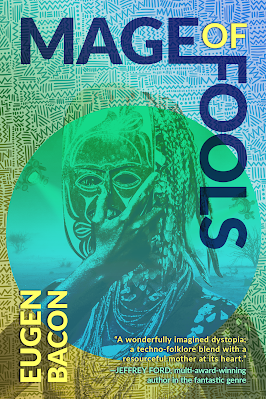

We're happy to help Meerkat Press support the release of their latest title Mage of Fools by participating in their blog tour. And if you're at all into winning free stuff, they're running a giveaway where you can potentially win a $50 book shopping spree.

Click here to enter!

Welcome to our Indie Spotlight series, in which TNBBC gives small press authors the floor to shed some light on their writing process, publishing experiences, or whatever else they'd like to share with you, the readers!

Today, we are shining the spotlight on Eugen Bacon

Eugen Bacon is an African

Australian author gradually growing her black speculative fiction writing in

novels, novellas, short stories, essays and prose poetry to a global gaze. She

was recently announced in the honor list of the 2022 Otherwise Fellowships, and

appears in four works shortlisted in the 2021 British Science Fiction Awards,

including her collections Danged Black

Thing (2021) by Transit Lounge Publishing and Saving

Shadows (2021), a collection of

black speculative prose poetry and microlit by NewCon Press, for Best Art.

Publishers Weekly listed

her newest novel Mage

of Fools in the Top 10 SF, Fantasy

& Horror Books Spring 2022.

Eugen’s debut novel Claiming T-Mo (2019)

by Meerkat Press is a Jekyll-and-Hyde conundrum that happens when a father

flouts the conventions of a matriarchal society. The story tackles themes of identity,

engaging with difference, betwixt, inhabitation, a multiple embodiment—recurring

themes in Bacon’s storytelling.

Eugen is fond of poetry

for its abstract, fluid and subversive nature, and says, “Poetry is timeless,

intense, insistent and metaphoric. It comes with immediacy and you can write it

from the gut.”

Let’s chill out with Eugen,

find a little more about her interests:

Why speculative fiction?

I’d define my writing literary speculative fiction,

where poeticity, musicality of the text and playfulness with language is a

penchant. In a form of subversive activism, speculative fiction empowers a

different kind of writing with its unique worldbuilding that has, over decades,

emboldened writers like Octavia Butler and Toni Morrison to write a different

kind of story that’s also about writing oneself in.

Where is your writing space?

My writing begins in the head and on scraps of

paper, scribbles in notepads everywhere. By the time I settle down to the

writing, it’s about putting the pieces together.

Writing ritual?

Increasingly I find myself experimenting with

prose poetry that sometimes slips into the opening, closing, sideline or core

of a story. Sometimes I write to music, or the news—where else would I find stories

of carnage?

Writerly crush?

Toni Morrison. In shaping my own voice, I was

drawn to writers of literary fiction, counting Anthony Doerr and Michael

Ondaatje, and found commonalities in riveting

dialogue; in the depth of characterisation; in the ambition, adventure and

variability of writing that discourages bad writing. These favourite authors seduce

me with bold writing that spotlights mood, reorients prose and courts

characterisation. They anticipate me, the reader, until I mislay questioning

and instead find curiosity.

Are you structured or unstructured as

a writer?

It’s increasingly a balance of both. I am an

experimental writer. I love to explore the uncanny and step beyond traditional

expectations of genre. I am enchanted with language (Morrison), and playfulness

with text (Roland Barthes), each taking me to a space where I can be, become,

and my characters can be, they can become.

A short story or prose poetry begins with a

question, or a curiosity. I am seeking to find something, and sometimes I don’t

know what it is. It may be a longing or a memory, a dirge or a possibility. The

quest is fluid, and I am open to where it might take me – sometimes to a newer

question, or curiosity.

It is intentional when I write a novella or a

novel, because I chart its skeleton and have an idea of its core players, of

the events that might drive them and, vaguely, why. Often, I tuck little

stories and poems inside, layered vignettes invisible to the reader, but they

carry the mutability and intensity of a short story, which seems to power my

longer forms.

If you could improve your writing

right now…

A part of me would love to have the craft and

patience to write a series maybe. But that’s not telling it straight. The short

form is my love and, at 49,000 words of a novel, it’s Mt Kilimanjaro.

When I’m not writing…

I am reading—I love short stories, collections,

anthologies, black spec fic poetry. I love watching a film or documentary that

moves me or triggers my mind (nothing is waste), and fine dining (but, the pandemic).

Reading right now…

Susan Midalia is a titillating Australian short

story writer, and she brings me back to my fondness of the short story. She’s

not a speculative fiction writer and her literary shorts—about 2,000 words each

or so—are something else! My favourite is An Unknown Sky and Other Stories.

Best film…

I’d like to start with Matrix, which I

love, but no. John Carter, an adaptation of Edgar Rice Burroughs A

Princess of Mars, moves me in many ways.

In your writing, what are you most

proud of?

I’m truly happy with where I am at in my

writing, the global visibility that my work is getting and the publishers it is

attracting. Danged Black

Thing was my biggest breakthrough in Australia. I’m

excited about Mage of Fools by Meerkat Press, the publisher who made me.

I like how my upcoming collection Chasing

Whispers (2022) by Raw Dog Screaming Press is turning out. Despite the pandemic,

I have managed to be incredibly prolific, and I am grateful to my ancestors and

all the generous readers, critics, writers, editors and publishers who extend

to me many opportunities that thrive me.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Releases March 15, 2022

Speculative Fiction | Dystopian | Afrofuturist

SUMMARY:

In the

dystopian world of Mafinga, Jasmin must contend with a dictator’s sorcerer to

cleanse the socialist state of its deadly pollution.

Mafinga's

malevolent king dislikes books and, together with his sorcerer Atari, has

collapsed the environment to almost uninhabitable. The sun has killed all the

able men, including Jasmin’s husband Godi. But Jasmin has Godi’s secret story

machine that tells of a better world, far different from the wastelands of

Mafinga. Jasmin’s crime for possessing the machine and its forbidden literature

filled with subversive text is punishable by death. Fate grants a cruel

reprieve in the service of a childless queen who claims Jasmin’s children as

her own. Jasmin is powerless—until she discovers secrets behind the king and

his sorcerer.

BUY LINKS: Meerkat Press | Amazon | Barnes & Noble

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

EXCERPT:

1

Tuesday.

Outside the double-glazed window, a speck

grows from the moonless night and yawns wide, wider, until its luster washes

into the single-roomed space, rectangular and monolithic. One could mistake the

room for a cargo container.

The space, one of many units neatly rowed

and paralleled in Ujamaa Village, pulses for a moment as the radiance outside

grows with its flicker of green, yellow and bronze. The cocktail of

incandescent light tugs along a tail of heat. Both light and heat seep through

the walls of the khaki-colored shelter, whose metallic sheen is a fabrication,

not at all metal.

Light through the window on the short face

of the house—the side that gazes toward Central District in the distance—rests

on the luminous faces of a mother and her two young children, their eyes pale

with deficiency in a ravaged world. It’s a world of citizens packed as goods in

units whose short faces all stare toward the Central District that will shortly

awaken in the dead of the night. The light drowns the toddler’s cry of wonder.

As sudden as the ray’s emergence, it

evanesces and snatches away its radiance, leaving behind hoarfrost silence. A

sound unscrolls itself from the darkness outside. First, it’s a thunderhead

writing itself through desert country—because this world is dry and naked,

barren as its queen.

The lone cry of a wounded creature, a howl

or a wail reminiscent of the screech of a black-capped owl, plaintive yet

soulful, rises above the flat roofs screening the wasted village. The cry is a

dirge that tells an often-story of someone in agony, of a hand stretched out to

touch an angel of saving but never reaches. A second thunderhead slits the

sound midcry, nobody can save the mortally wounded one.

Jasmin closes her eyes. She needs no one to

tell her. She knows.

Everybody knows—except the children. That

King Magu’s guards—so few of them, yet so deadly—have found another story

machine, and its reader.